Inspired by Shannon Vallor’s book “Technology and the virtues: A philosophical guide to a future worth wanting“, I am writing a series of short portraits of people who can be viewed as ‘exemplars’ of the technomoral virtues that she discusses (2016, p. 118-155):

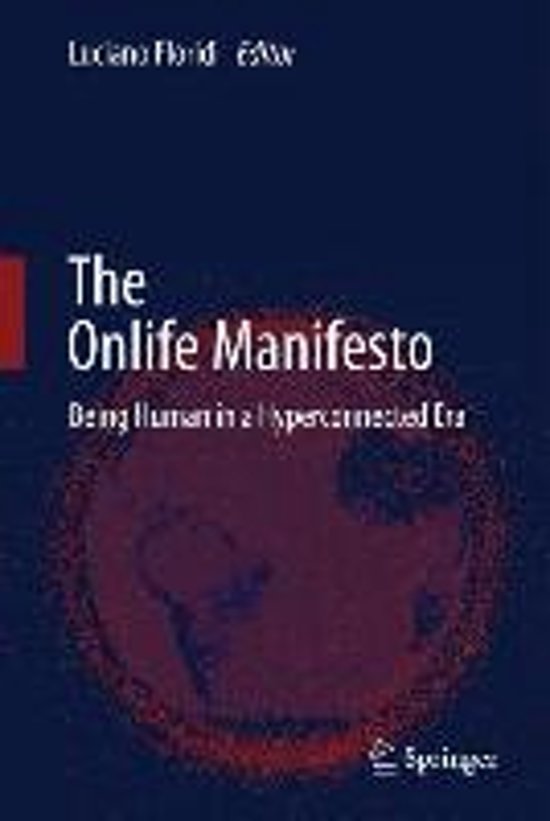

- Honesty: Respecting Truth: Cathy O’Neil, Luciano Floridi

“an exemplary respect for truth, along with the practical expertise to express that respect appropriately in technomoral contexts” (p. 122) - Self-control: Becoming the Author of Our Desires: Tristan Harris, Aimee van Wynsberghe

“an exemplary ability in technomoral contexts to choose, and ideally to desire for their own sakes, those goods and experiences that most contribute to contemporary and future human flourishing” (p. 124). - Humility: Knowing What We Do Not Know: Tristan Harris, Cathy O’Neil, Yuval Noah Harari, Kate Crawford

“a recognition of the real limits of our technosocial knowledge and ability; … and renunciation of the blind faith that new technologies inevitably lead to human mastery and control of our environment” (p. 126-7). - Justice: Upholding Rightness: Kate Raworth, Jaron Lanier, Cathy O’Neil, Luciano Floridi, Aimee van Wynsberghe, Edward Snowden, Safiya Umoja Noble, Bill Gates, Kate Crawford, Otto Scharmer

a “reliable disposition to seek a fair and equitable distribution of the benefits and risks of emerging technologies” and a “characteristic concern for how emerging technologies impact the basic rights, dignity, or welfare of individuals and groups” (p. 128). - Courage: Intelligent Fear and Hope: Cathy O’Neil, Sherry Turkle, Edward Snowden, Kate Crawford, Greta Thunberg

“a reliable disposition toward intelligent fear and hope with respect to moral and material dangers and opportunities presented by emerging technologies” (p. 131) - Empathy: Compassionate Concern for Others: Kate Raworth, Yuval Noah Harari, Sherry Turkle, Bill Gates

a “cultivated openness to being morally moved to caring action by the emotions of other members of our technosocial world” (p. 133) - Care: Loving Service to Others: Sherry Turkle, Aimee van Wynsberghe

“a skillful, attentive, responsible, and emotionally responsive disposition to personally meet the needs of those with whom we share our technosocial environment” (p. 138) - Civility: Making Common Cause: Tristan Harris, Sherry Turkle, Edward Snowden, Greta Thunberg

“a sincere disposition to live well with one’s fellow citizens of a globally networked information society: to collectively and wisely deliberate about matters of local, national, and global policy and political action; to communicate, entertain, and defend our distinct conceptions of the good life; and to work cooperatively toward those goods of technosocial life that we seek and expect to share with others” (p. 141). - Flexibility: Skilful Adaptation to Change: Jaron Lanier, Luciano Floridi

a “reliable and skillful disposition to modulate action, belief, and feeling as called for by novel, unpredictable, frustrating, or unstable technosocial conditions” (p. 145). - Perspective: Holding on to the Moral Whole: Kate Raworth, Jaron Lanier, Yuval Noah Harari, Luciano Floridi, Safiya Umoja Noble, Otto Scharmer

“a reliable disposition to attend to, discern and understand moral phenomena as meaningful parts of a moral whole” (p. 149) - Magnanimity: Moral Leadership and Nobility of Spirit: Edward Snowden, Bill Gates, Otto Scharmer, Greta Thunberg

My goal, with these portraits, is to inspire researchers, engineers, developers and designers to cultivate these virtues, in themselves and in their work.

Portraits written: Tristan Harris; Kate Raworth; Jaron Lanier; Cathy O’Neil; Yuval Noah Harari; Sherry Turkle; Luciano Floridi; Aimee van Wynsberghe; Edward Snowden; Safiya Umoja Noble; Bill Gates; Kate Crawford, Otto Scharmer. I plan to write portraits of the following people (in the course of 2019): Greta Thunberg, John Havens, Mariana Mazzucato, danah boyd, Mireille Hildebrandt, Marleen Stikker and Douglas Rushkoff.

The people who develop technologies need to cultivate (some of) these virtues, in order to deliver technologies that indeed support others (‘users’) to cultivate the very same virtues. If you are working on an algorithm that can impact people’s lives in terms of justice, e.g., in law enforcement, regarding discrimination, fairness and equality, then you will need to cultivate the virtue of justice. Similarly for the other virtues.

One can cultivate virtues in two ways:

- By carefully watching and learning from ‘exemplars’, people who embody, exemplify or champion specific virtues (= list above), especially by watching or listening–that’s why there are links to presentations, interviews and podcasts;

- And by trying-out these virtues in one’s own life, and professionally in one’s projects–learning by doing, ‘practice makes perfect’; the aim is to align one’s thoughts, feelings and actions, so that a virtue becomes a virtuous habit.

Here are some suggestions for cultivating these virtues:

- Reflect on your current work as researcher, engineer, developer, designer; select one project in which you develop a technology, product or service

- Use your moral imagination to envision this technology’s impact in society and identify which one or two virtues are at stake, e.g., self-control (does the service aim to make people ‘addicted’, a.k.a. ‘engagement’), justice (can the service have unfair or discriminatory effects), civility (does the service enable people to ‘troll’ others or create ‘filter bubbles’), etcetera.

- Pick one or two exemplars from the list; people that embody, exemplify or champion the virtues that you want to know more about. Read their portraits and, if you have time, watch their TED Talk, read their books, listen to their podcasts, etc.

- Next time, in your project, you try-out the virtue(s) you are cultivating: speak up and defend self-control of ‘users’; make a case for justice in the data or algorithm you are using; build-in features that facilitate civility in communication; etc.

The cultivation of these virtues is not a nice-to-have add-on. It is imperative that we take our responsibility (noblesse oblige) and act responsibly:

“The challenge we face today is not a moral dilemma; it is rather a moral imperative, long overdue in recognition, to collectively cultivate the technomoral virtues needed to confront [diverse and urgent] emerging technosocial challenges wisely and well.” (Vallor, 2016, p. 244).

From: https://twitter.com/katecrawford

From: https://twitter.com/katecrawford

From:

From:

From: https://sherryturkle.com/

From: https://sherryturkle.com/